VB News Desk: What Is Ebola?

Posted on 8/17/19 by Lukas Bowditch

If you’ve been keeping up with recent global medical news, you may have noticed that Ebola has been making a comeback over the past couple of months. The last time Ebola was a significant concern was 2013-2016, during the Western African Ebola virus epidemic, but more recently, the WHO declared Ebola an international health emergency on July 17, 2019.

Ebola is a rare but deadly disease caused by viruses in the genus Ebolavirus. The disease initially is transmitted by an animal (such as a bat or primate) to a human, then from humans to other humans by direct contact with bodily fluids or objects contaminated with them.

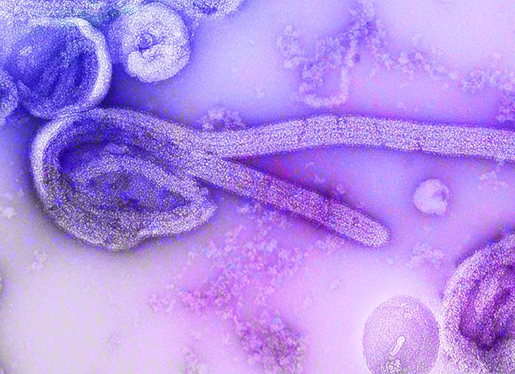

An electron microscope image of the 1976 isolate of Ebola.

An electron microscope image of the 1976 isolate of Ebola.

Image from the CDC's Public Health Image Library.

Once someone has Ebola, they may experience violent and possibly deadly symptoms, such as fever, muscle pain, diarrhea, vomiting, and hemorrhages. The hemorrhages from Ebola can be external, which causes the gruesome effect of bleeding through the eyes, nose, or other orifices.

Since Ebola is such an overpowering disease, it’s difficult to tease out each step of how someone goes from healthy to internally bleeding.

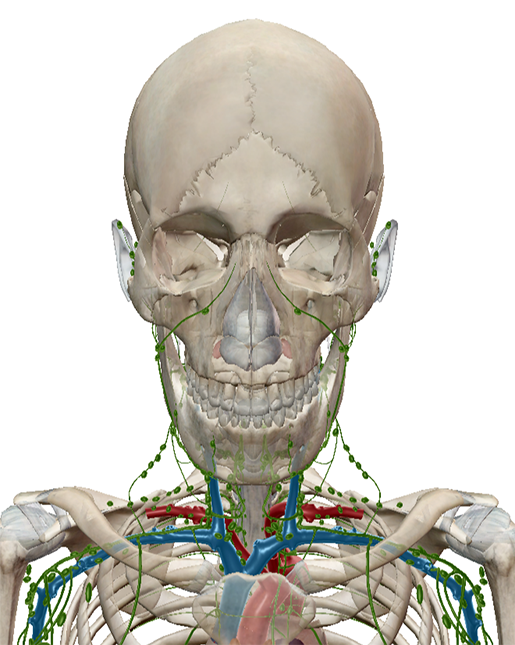

We do know that Ebola cripples the immune system. Macrophages become infected when they arrive at the site of the initial infection and engulf virus particles. Infected dendritic cells can’t give the proper signals for T cells to combat the infection. Also, as lymphocytes (some of which are antigen-presenting cells, or APCs) become infected, many of them die via apoptosis. This means that the virus can replicate very quickly as the immune system fails to mount a proper defense.

Lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

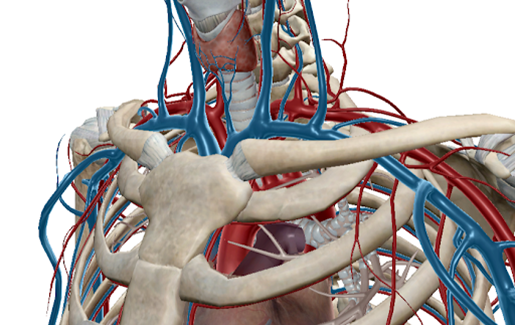

After infecting the immune system, Ebola can start to wreak havoc on other parts of the body as it moves through blood and lymph. Damage to the blood vessels causes them to become leaky, resulting in hemorrhaging. Nitric oxide released by infected macrophages contributes to this. Infected macrophages also release proteins that cause coagulation, forming blood clots and reducing blood supply to organs. In addition, immune cells that don’t undergo apoptosis can burst, spreading the virus and inflammatory proteins further.

Blood vessels. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Blood vessels. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Eventually, damage to hepatocytes in the liver impairs the blood’s ability to clot and the blood vessels continue to hemorrhage. Blood supply to organs is further reduced when damage to cells in the adrenal glands causes blood pressure to become even lower. Ultimately, death from Ebola is a result of shock and multiple organ failure.

As scary as Ebola may sound, it’s probably not something to stress over during your day-to-day life if you do not live in an area where there is a large-scale outbreak. For one, the virus isn’t airborne—it spreads only through animal contact or fluid-to-fluid contact.

That being said, it still has the potential to be incredibly dangerous when an outbreak does occur—especially when compounded with the issues poverty brings. For example, the current outbreak is centered around the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and over 1,000 lives have been claimed. It previously spread into Uganda, but they’re now Ebola free.

The current outbreak differs from the last major Ebola epidemic in that there is now an Ebola vaccination. The vaccine is administered to those who may be at risk, and then to their contacts. The vaccine is shown to be over 97% effective, although there are concerns about the supply being unable to keep up with the need. Another large problem with administering the vaccine is the high level of violence in the region, even against health workers. This is concerning when trying to rally international support for the cause against Ebola. Lastly, locals in the region don’t necessarily trust the Ebola vaccine, which makes it harder to widely administer.

Over the last few weeks, the situation in the DRC has been improving. As of August 11, more than 1,300 people have been vaccinated in Goma, a large city and travel hub near Rwanda. No new cases of Ebola have been reported in Goma since August 2. In addition, two new drugs are now being used to treat Ebola patients in the DRC. The BBC reports that "more than 90% of infected people can survive if treated early with the most effective drugs."

Hopefully, through the hard work of the local and international health communities, the disease can once again be stopped.

Want to learn more about how the immune and circulatory systems work? Check out these VB Blog and Learn Site resources:

- Reacting and Adapting to Disease: How the Immune System Works

- The Lymphatic System: Innate and Adaptive Immunity

- Blood Vessel Structure and Function: How the Circulatory Network Helps to Fuel the Entire Body

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.