VB News Desk: How Much Artificial Sweetener Is in Your Food?

Posted on 11/5/19 by Laura Snider

The American Academy of Pediatrics recently released a policy statement regarding the use of nonnutritive sweeteners. It’s a great summary of the available literature on these types of additives, but it also makes several important points about the presence of artificial sweeteners in consumer products (not just food and beverages, but mouthwash, too!).

The most startling of these is that although manufacturers have to report that a product contains artificial sweetener(s), they aren’t required to report the amount of these sweeteners that they’ve used. Because of this, it’s difficult to know for sure exactly how much artificial sweetener people are consuming.

Today, we’re going to summarize some of the takeaways from this policy statement, and learn all about artificial sweeteners along the way!

What is a nonnutritive sweetener?

The breakdown of sweetener types basically looks like this:

- Sugars

- Ex: brown sugar, cane sugar, fructose, high fructose corn syrup

- Alcohol sugars:

- Ex: isomalt, maltitol, mannitol, sorbitol, xylitol

- Nonnutritive sweeteners (NNSs):

- Ex: saccharin, aspartame, acesulfame potassium, sucralose, stevia, neotame, advantame

Nonnutritive sweeteners are defined in the AAP statement as “high-intensity sweeteners that provide a sweet taste with little to no glycemic response and few to no calories.” Currently, acesulfame potassium, advantame, aspartame, neotame, saccharin, and sucralose are approved for consumption by the FDA. Stevia and luo han guo (monk fruit) extract have a GRAS (generally recognized as safe) designation.

Nonnutritive sweeteners vs. caloric sugars

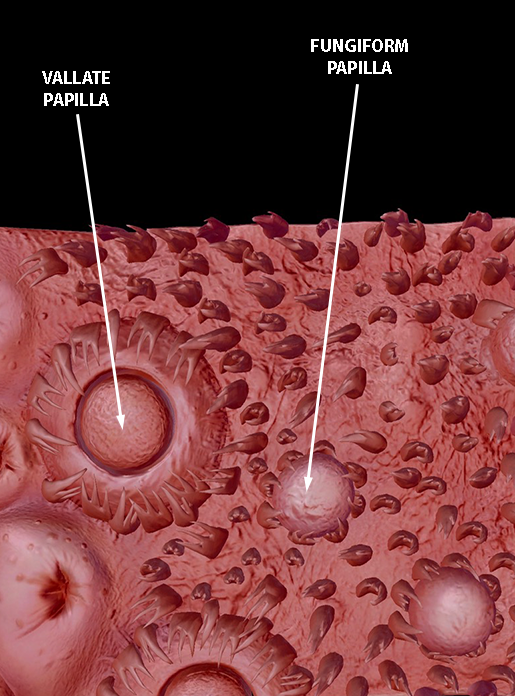

The dorsal and lateral surfaces of the tongue are covered with little protrusions called papillae. These aren’t your tastebuds, but many of them do contain tastebuds. The vallate papillae contain about 100-300 tastebuds each, and the fungiform papillae have around 5 tastebuds each.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Tastebuds contain taste receptor cells, which detect different types of tastes (sweet, bitter, salty, sour, or umami). In addition to the ones on your tongue, there are also taste receptors in the oropharynx and intestines.

Sweet-taste receptors “can bind to chemicals of widely varying structures, including the caloric sugars (e.g. sucrose, glucose, and fructose), sweet proteins such as thaumatin and monellin, and non-nutritive sweeteners.” This is why your brain tells you that—just like regular sugars—NNSs are sweet! Fun fact: aspartame doesn’t stimulate sweet taste receptors in mice, so they don’t perceive it as sweet and don’t show behavioral responses to it.

Do nonnutritive sweeteners change taste preference or appetite?

The AAP states that “data suggest but do not conclusively demonstrate that NNS use may promote the intake of sugary food and drink by affecting taste preferences.” It could be the case that the intense sweetness of NNSs overstimulates the sweet taste receptors, causing us to perceive other, healthy foods (such as fruit) as less sweet. Another possibility is that frequently consuming NNSs could cause our association between sweetness and calorie intake to weaken, leading us to crave and consume more sugary foods and beverages.

However, as it stands right now, there isn’t any research to conclusively prove a causal link between NNS consumption and these types of appetite changes.

Some studies have also examined whether nonnutritive sweeteners have physiological effects on the metabolism of glucose. However, a large meta-analysis by Brown & Rother (2012) suggest that, as of the time their paper was written, there was “insufficient evidence to support an effect of non-nutritive sweeteners on intestinal glucose absorption in healthy humans.”

Are nonnutritive sweeteners dangerous?

The claim that “artificial sweeteners are going to give us all cancer” is pretty well ingrained into the public consciousness, at least here in the US.

It might surprise you to learn that this statement isn’t really backed up by the current body of research on the potentially harmful effects of NNSs. While a link between NNS use and cancer is possible, “the long latency period, the penetrance of NNSs into the food supply (making it difficult to isolate an adequate unexposed control group), and the diversity of potential mechanisms have made it difficult to definitively exclude potential carcinogenic properties of NNSs but also make it difficult to conclude that there is any such association.”

In short, a connection between NNSs and cancer (and many other health outcomes) has been difficult to prove, but also difficult to disprove. Additionally, the effects of consuming large amounts of NNSs over many years are still unknown. More data—and more importantly, more good data—will be necessary for drawing any definitive conclusions.

One thing we do know for sure is that people with phenylketonuria (PKU) shouldn’t consume aspartame because it contains phenylalanine, which their bodies can’t break down.

Are there benefits to consuming nonnutritive sweeteners?

The main benefit to NNSs is that they offer a sweet flavor without the calories. There is some evidence to suggest that NNSs can aid in weight loss. However, though many short-term studies seem to show a weight-loss benefit to NNS consumption, there isn’t much reliable data on the long-term weight-loss effects. For example, the AAP statement reported that in children, “NNS use may prevent excess weight gain over a period of 6 to 18 months but [...] in general, studies evaluating the relationship between NNS intake and obesity are lacking rigor.”

While much of the existing data is insufficient to prove various claims about the health effects of nonnutritive sweeteners, the AAP statement makes one thing abundantly clear: the FDA should require that product labels list the type(s) and quantity of NNS they contain. This will help consumers to better monitor their NNS intake and make the potential risks and benefits of NNS use easier to study (especially if the method of data collection involves study participants reporting on their dietary habits).

Hopefully, future research will give us more consistent, conclusive data on these ubiquitous food additives!

Want to learn more about the tongue and how the body perceives taste? How about how the body regulates blood glucose levels? Check out these resources from the VB Blog and Learn Site:

- Anatomy and Physiology: The Terrific Tongue

- Sight, Sound, Smell, Taste, and Touch: How the Human Body Receives Sensory Information (Learn Site)

- The Precious Pancreas: Insulin, Glucagon, and Digestive Juices

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources:

“The Organization of the Taste System.” Neuroscience (2nd ed.) Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al., editors. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2001.