The Biome Inside You: An Introduction to Gut Flora

Posted on 10/21/22 by Sarah Boudreau

The nineteenth century poet Walt Whitman famously wrote “I am large, I contain multitudes,” and though he wrote that over a hundred years before scientists recognized the microbiome, he was definitely on to something.

The human body contains over 100 trillion microbes, which in total weigh as much as five pounds, and there are actually 200 times the number of microbe genes than human genes in your body. Some go as far to call the gut microbiome, the microorganisms in the gastrointestinal tract, “the sixth vital organ."

When we talk about the microbiome, it’s usually in reference to the gut microbiome, or gut flora. Over the past ten years, there’s been an explosion of research into the gut microbiome. As one researcher wrote, “Between 2013 and 2017, the number of publications focusing on the gut microbiota was, remarkably, 12,900, which represents four-fifths of the total number of publications over the last 40 years that investigated this topic.”

But exactly what is the gut microbiome? What does it do for the human body? And does that Jamie Lee Curtis yogurt actually do anything?

Let’s dive in.

Your own personal forest of microbes

The human body is home to bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and viruses, but when we’re talking about gut microbiota, bacteria steals the show. There are between 500 and 1,000 species of bacteria in the GI tract.

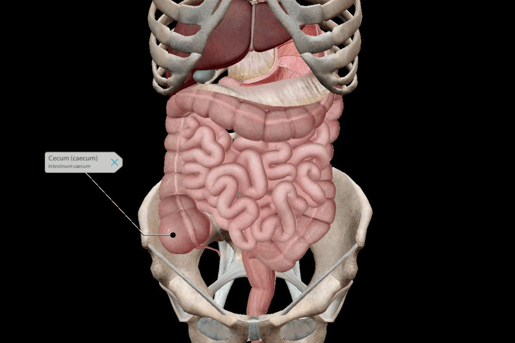

The majority of the microbes in your intestines are in your cecum, a part of the large intestine. The cecum is a pouch-shaped structure that connects the small intestine to the colon.

Image from VB Suite.

Image from VB Suite.

Gut microbes interact with almost all of the body’s cells, not just the cells in the gut. Gut microbes affect other organs by stimulating enteroendocrine cells to create hormones. It’s even thought that some gut bacteria can communicate with human cells to some extent, promoting immune reactions.

We often think about microbes as invaders entering our bodies to wreak havoc, but many microbes are beneficial to humans. In fact, in many ways, our bodies are built around the existence of gut microbes; some gut microbe species and humans evolved alongside each other. Researchers found that microbes that evolved with people have smaller genomes and greater oxygen and temperature sensitivity, while other microbes have traits of bacteria that live outside the body. We have a symbiotic relationship with these “good” microbes, where they get food and a place to live and we reap many benefits from their existence.

Gut bacteria helps gut function in several ways, such as:

- Regulating gut motility

- Metabolizing substances foreign to the body

- Activating and destroying toxins

The gut microbiome develops when we’re very young: the baby gets its first microbes by passing through the birth canal. This means that babies delivered via c-section can miss out on those early microbes: a study found that c-section babies and vaginally delivered babies have stark differences in their gut microbiomes, though over time they grow more similar.

The environment also influences gut microbiomes when we're children. Kids living with dogs have a lower chance of having a respiratory disorder, as the presence of dogs can increase bacteria diversity. Growing up in a rural area or farm can also create a microbiome that reduces the risk of inflammatory respiratory disease.

We aren’t certain on the timeline of gut flora development, but sometime in early childhood, the microbiome settles down. By adulthood, it becomes stable, with few fluctuations.

A healthy population of gut bacteria

What does a healthy microbiome look like? It is extremely hard to say. This question stumps scientists because among healthy people, gut microbiomes look extremely different from person to person. When it comes to gut bacteria, we have so many questions that still need to be answered.

We do know of some factors that influence gut microbiota in adulthood, including antibiotics and other drugs. Though it’s obvious that antibiotics influence microbiota (It’s right in the name!), some other drugs that have nothing to do with bacteria have been found to impact our microbiomes.

People in different countries have different microbial makeups, which is one clue that diet plays a very important role in developing microbiomes. For example, a high fiber diet may encourage certain gut bacteria to flourish.

However, the microbiome’s relationship with diet is such a complex topic that it’s hard to draw many prescriptive conclusions.

.jpg?width=515&name=My%20project%20(31).jpg) Image from VB Suite.

Image from VB Suite.

Despite this, gut health is having a bit of a moment. Gut health is one of the most recent health and wellness trends that flood social media with influencers promoting so-called health products. On TikTok, videos with the #guttok tag have a staggering 400 million views, and the grocery store is full of products claiming to help your gut, including tons of “probiotic” products like yogurt.

Let’s clear the air: despite the hype, there’s zero proof that people with normal GI tracts benefit from taking probiotics. In fact, the strains of bacteria manufacturers put into the yogurt probably can’t survive the stomach’s acid level, and even if a few manage to survive, they would not have a noticeable impact on the composition of the microbiome.

A new frontier—and many barriers—for research

Despite flashy headlines, research on gut bacteria can be complicated.

Researchers have found links between gut microbiota and a great number of diseases, like inflammatory bowel diseases, diabetes, chronic heart diseases, and HIV.

Researchers also say that there’s an association between metabolic disorders (i.e., diabetes) and microbiome shifts at the phylum level. However, they’re trying to puzzle their way through many other questions. Do they need to look at the genus and species levels? Do the total number of microbes matter, or the proportion of one type of microbe to other types? What about the activity levels of the microbes?

Correlations have been found between gut microbiota and scores of different diseases, but as one researcher writes, “[W]hen a correlation is found between a given microbe and a disease or healthy situation, it is challenging to show the exact implication of the candidate on the onset of the disease or conversely its beneficial impact.”

In other words, correlation does not imply causation, and there’s a lot we don’t know. The author uses the example of two proof-of-concept studies: one that stated that P. copri improved glucose and insulin sensitivity and one that stated that P. copri caused glucose intolerance and decreased insulin sensitivity. This drives home how complicated the gut microbiome really is.

When studying the microbiome and disease, researchers also run up against a “chicken or the egg” problem: did the disease cause the altered microbiome or did the altered microbiome cause the disease?

We are getting better at doing DNA sequencing on the bacteria we do find, but right now, we aren’t as good at studying non-bacteria gut microbes. Furthermore, a lot of research has been limited to the types of gut bacteria we can grow in a lab. These limitations make firm conclusions difficult.

Looking to the future

On the more practical side of things, one interesting medical procedure involving the microbiome is the fecal transplant—that’s right, this procedure puts donated poop into another person's intestines. This is usually used to treat people with persistent C. diff infections, since the microbiota from the healthy person is transmitted into the C. diff person to help override the “bad” bacteria with “good” bacteria. Recently, however, researchers have tried using fecal transplant for patients with ulcerative colitis. In 2017, almost a third of participants went into full remission after the transplant.

In 2022, scientists announced that they have created a human microbiome from scratch using 119 bacteria species. When introduced to mice who did not have a microbiome, the transplanted artificial microbiome took root. It caused those mice to develop healthy immune systems. With a synthetic microbiome, we can better study the roles of individual microbes. Developments like this are a big step forward in the study of gut bacteria and how it influences our lives and health.

Read more about digestion on the Visible Body Blog!

- Anatomy & Physiology of Digestion: 10 Facts That Explain How the Body Absorbs Nutrients

- VB News Desk: The Secret to Athletic Performance Enhancement Could Be in Marathon Runners' Guts

- IBS and IBD: What's the Difference?

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology or biology course! Learn more here.