Three Key Facts About Cystic Fibrosis

Posted on 5/14/21 by Laura Snider

As you might already be aware, May is Cystic Fibrosis Awareness Month. Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is a rare, progressive disease characterized by persistent lung infections and breathing difficulties that worsen over time. In this blog post, we’ll go over the basics of cystic fibrosis. We’ll discuss the symptoms of CF, what causes it, how it affects the digestive system in addition to the respiratory system, and how treatment options have progressed since the mid 20th century.

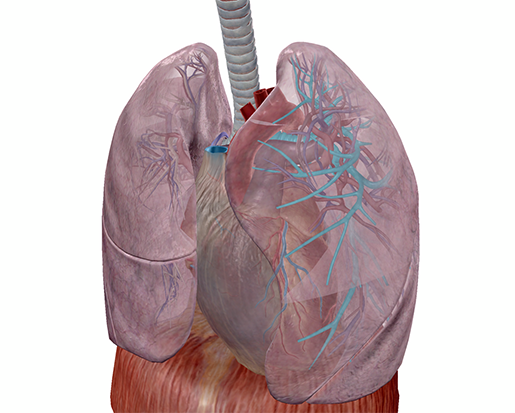

Bronchi of the left lung, highlighted. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Bronchi of the left lung, highlighted. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

According to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, symptoms include:

- Very salty-tasting skin

- Persistent coughing, at times with phlegm

- Frequent lung infections including pneumonia or bronchitis

- Wheezing or shortness of breath

- Poor growth or weight gain in spite of a good appetite

- Frequent greasy, bulky stools or difficulty with bowel movements

Frequently, males with CF experience infertility as well.

Currently, there are around 70,000 people around the world living with cystic fibrosis, and about 1,000 new diagnoses are made each year. Most people (75%) with CF are diagnosed before they are two years old. Unfortunately, CF comes with a reduced life expectancy—some people with this disease live into their 50s and 60s, but many pass away earlier than that. Although research has brought forth many new treatment options over the years, allowing folks with CF to live longer, healthier lives, there is not yet a cure.

1. Cystic fibrosis is an inherited disorder involving mutations to both copies of the CFTR gene.

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disorder. It is caused by mutations to the gene that produces the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein—or the CFTR protein, for short. There are around 1700 different mutations to this gene that can cause CF.

Not everyone with mutations to the gene that produces CFTR has cystic fibrosis. This is because CF is a recessive genetic disorder. People have two copies of each gene (because they have two copies of each chromosome—one from their mother, and one from their father). Someone with a mutation on only one copy of the CFTR gene is considered a carrier of cystic fibrosis, but they won’t have the disease. In order to have cystic fibrosis, a person needs to have two copies of CFTR with mutations. If two carriers of CF have a child, there is a 25% chance that their child will have cystic fibrosis, a 50% chance that they will be a carrier, and a 25% chance that they will neither have CF nor be a carrier.

So what is it about the CFTR gene that causes CF? The CFTR protein regulates the movement of salt (NaCl) across membranes. When salt can't move across a membrane, it will build up on one side. This means that water won’t move properly across that membrane either, since water will generally flow from the side that has a lower concentration of salt to the side with a higher concentration.

The buildup of salt is what causes salty sweat in people with CF. A lack of water getting where it needs to go when mucus is secreted is the reason that mucus in the body—especially the mucus found in the airways of the respiratory system—becomes thick and sticky, building up and blocking the airways and other ducts in the body.

Mucus in the airways usually traps foreign materials and is subsequently moved to the pharynx, by the movement of projections called cilia, to be coughed up or swallowed. In CF, pathogens become trapped in the thicker mucus, which is more difficult for the cilia to move. Since the mucus can’t be expelled, the pathogens aren’t successfully removed from the body. This leads to the frequent lung infections that characterize the disease.

Mucus trapping foreign materials and cilia sweeping mucus upwards in the respiratory tract. Video footage from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Mucus trapping foreign materials and cilia sweeping mucus upwards in the respiratory tract. Video footage from Human Anatomy Atlas.

2. Cystic fibrosis doesn't just affect the respiratory system.

Thick, sticky mucus leads to problems outside the respiratory system as well. The digestive system, specifically the pancreas, is negatively affected by CF.

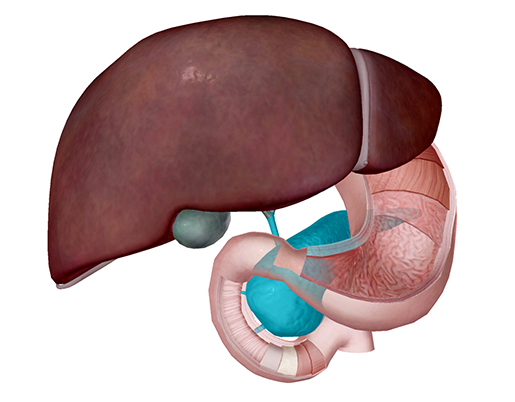

The pancreas in context with the other accessory digestive organs and the first portion (duodenum) of the small intestine. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The pancreas in context with the other accessory digestive organs and the first portion (duodenum) of the small intestine. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

In its role as an accessory digestive organ, the pancreas produces and secretes enzymes that help with the chemical breakdown of food in the small intestine. These enzymes get from the pancreas to the small intestine via small tubes—the pancreatic duct and the common bile duct.

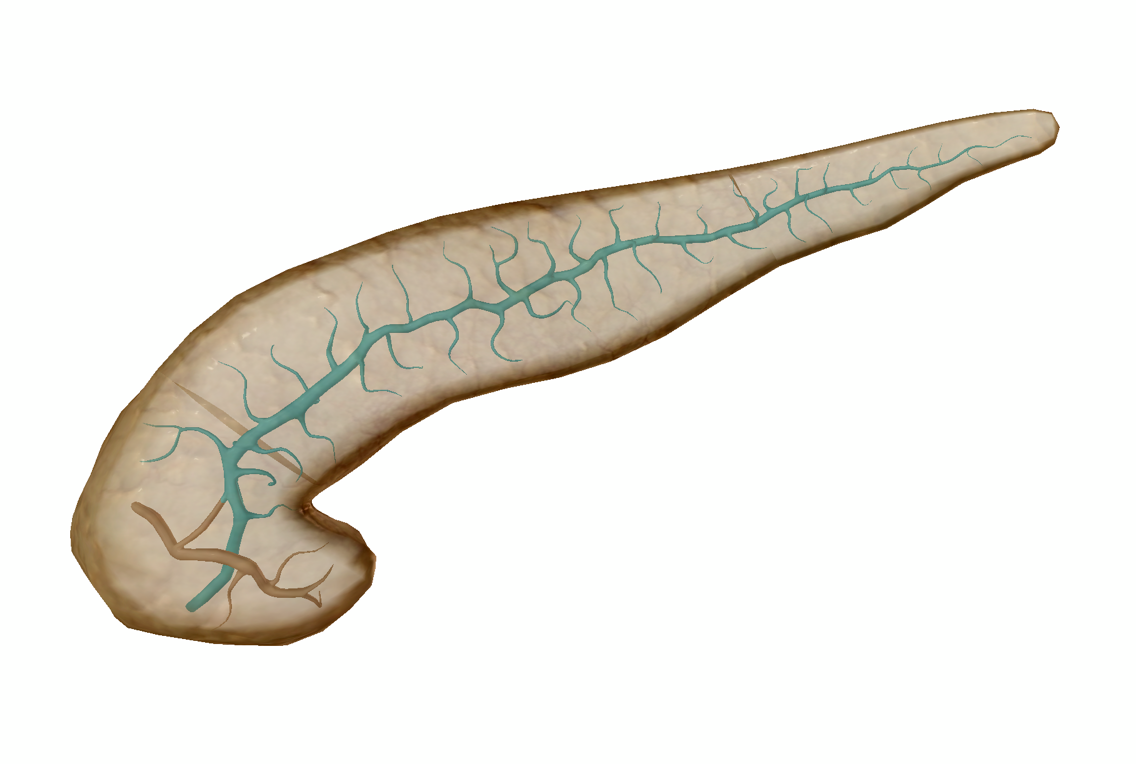

The main pancreatic duct. This duct connects to the common bile duct and its contents empty into the duodenum. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The main pancreatic duct. This duct connects to the common bile duct and its contents empty into the duodenum. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Cystic fibrosis can cause these ducts to become clogged with sticky mucus, meaning that the flow of pancreatic juice into the small intestine is impeded. This leads to digestive problems such as greasy or bulky stools, constipation, nausea, a loss of appetite, and more. The pancreas itself can also become inflamed due to the buildup of digestive fluid inside it.

Pancreatic insufficiency occurs in around 85% of adults with CF. To aid in digestion, many people with cystic fibrosis take pancreatic enzymes as a supplement.

In addition to its digestive function, the pancreas has an endocrine function as well: it secretes hormones that regulate blood sugar levels. Perhaps the most notable of these is insulin. Inflammation and scarring of the pancreas as a result of CF can impair insulin production, leading to a condition called cystic fibrosis related diabetes, or CFRD. CFRD is similar to type 1 diabetes, in that insulin production is reduced, but CFRD is different from both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. CFRD is often treated with insulin injections.

3. Research has led to improved treatments and longer lives for people with CF.

Since the 1950s, life-expectancy for people with CF has increased dramatically thanks to dedicated research that has led to new treatments. Before serious CF research really got started and before dedicated care centers were established, the life expectancy for someone with CF was only about a year. In 1962, someone with CF was only expected to live to be around 10 years old. In 1989, the CFTR gene and its role in CF was discovered, and the 1990s saw the first dedicated drugs for CF treatment. 2019 marked a particularly important treatment milestone—in October 2019, the FDA approved Trikafta, a triple combination therapy for CF, for use in CF patients over 12 years old with at least one copy of the F508del mutation (the most common CF mutation). You can find a comprehensive list of drugs and therapies that are in development, as well as those that are already in use, here.

Most people being treated for CF establish a personalized plan with their healthcare team. This can include a wide range of therapies such as airway clearance techniques, bronchodilator medications, medications to thin mucus (usually inhaled/delivered through a nebulizer), CFTR modulator medications (Trikafta is an example), pancreatic enzyme supplements, and personalized fitness and nutrition plans.

Bronchodilation in action. Video footage from Physiology & Pathology.

Bronchodilation in action. Video footage from Physiology & Pathology.

If you’re looking for ways to help boost awareness or you want to learn more about current CF research, check out the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s website here. The UK has a similar organization called the Cystic Fibrosis Trust.

Want to learn more about the respiratory and digestive systems, as well as pathologies affecting them? Check out these related VB Blog posts:

- Anatomy and Physiology of the Lower Respiratory System

- Anatomy and Physiology: Major Components of the Digestive System

- Exploring Lung Pathologies with Physiology & Pathology

- The Precious Pancreas: Insulin, Glucagon, and Digestive Juices

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.