Frightful Physiology: How Horror Movies Scare Us and Why We Can’t Get Enough

Posted on 10/29/21 by Sarah Boudreau

You know that feeling when the killer or the monster is creeping around the corner, ready to attack its next victim? Your heart races, your breath quickens, and for a moment it feels like you are the one in danger instead of the doomed character.

For as long as there have been movies, moviegoers have had physical reactions to what they see on the screen. Some reported that in 1931, when the original Dracula was first released, ambulances would park near the theaters to tend to passed-out moviegoers, and there are scores of stories of people fainting, panicking, or bolting from showings of The Exorcist.

Photo by Ron Lach from Pexels.

Photo by Ron Lach from Pexels.

These extreme reactions have become a part of horror movie lore and have been used by movie marketers for decades.

The classic Frankenstein begins with one of the actors addressing the audience out of character. He warns them about how scary the movie is: “I think it will thrill you. It may shock you. It might even horrify you. So, if any of you feel that you do not care to subject your nerves to such a strain, now's your chance to uh, well… we warned you.”

But if fear can really “subject your nerves to such a strain” and cause harm, what keeps us watching horror movies when we know we’ll be scared? In today’s blog post, we’ll talk about the body’s fear reaction and why some people find it so appealing.

The body’s reaction to fear

You’ve probably heard of “fight or flight,” which is the response the body has to stress. Stress is more than just cramming for a test—stress is a feeling of tension. And you know what definitely causes tension? Fear.

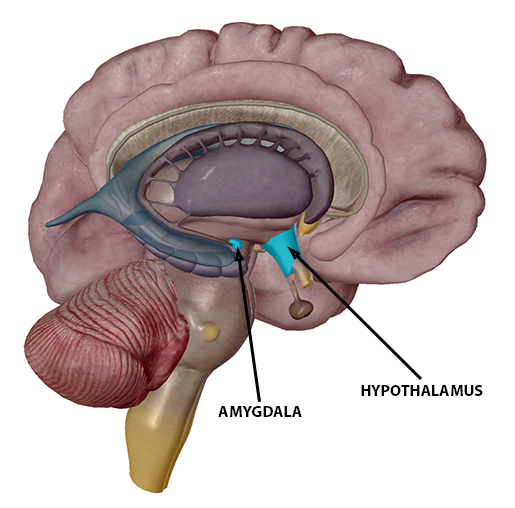

A chain reaction is triggered when you perceive a threat: first, your amygdala sounds the alarm. The amygdala is a part of your brain that, among other things, connects memory and emotion.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The amygdala calls upon the hypothalamus, which acts as your body’s switchboard, sending signals to the rest of your endocrine system. That’s how the message gets to the adrenal glands, and things start to get exciting.

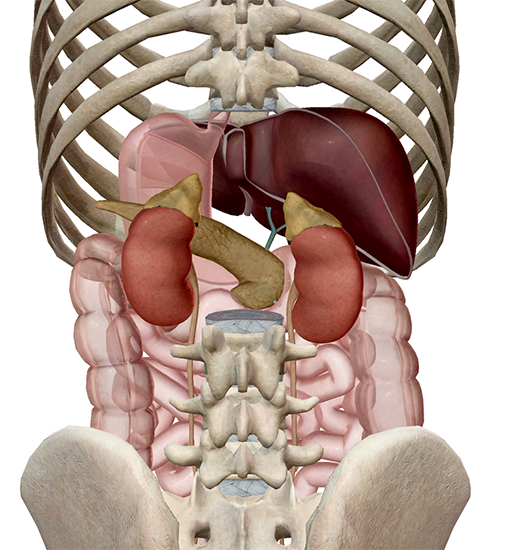

You have two adrenal glands, one atop each kidney, and they produce and release hormones directly into the bloodstream. These hormones affect a variety of bodily processes, but the most relevant here are cortisol (a glucocorticoid), epinephrine/adrenaline, and norepinephrine/noradrenaline.

In the stress response, the adrenal glands release epinephrine and norepinephrine into the bloodstream.

Posterior view of the adrenal glands, liver, and pancreas. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Posterior view of the adrenal glands, liver, and pancreas. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Epinephrine signals a number of changes in the body that you might recognize. Your lungs expand and the rate of respiration increases, so your body takes in more oxygen to deal with the threat. Your heart beats faster, your pupils dilate, and your muscles begin to tense up.

The body deems some functions like digestion unnecessary in a dangerous situation and begins to slow them down.

If the threat sticks around, the hypothalamus, pituitary, and adrenal glands get ready for round two.

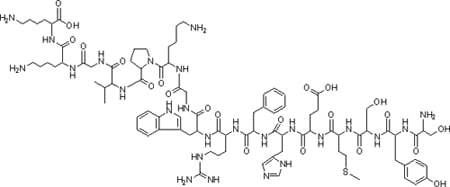

The hypothalamus releases a hormone called CRH (corticotropin-releasing hormone), which signals the pituitary gland to release ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone).

Image of ACTH from Wikipedia Commons.

ACTH in turn signals the adrenal glands to release cortisol, often called “the stress hormone.” Cortisol helps give the body the energy it needs to stay on high alert for a bit longer by signaling several organs in the body to make changes impacting blood glucose levels.

The stress response primes the body to deal with threats, optimizing it to flee or to fight.

Some people refer to being “paralyzed by fear,” which some researchers believe is a response that happens more commonly to a threat perceived as happening far away. Freezing in place can even happen when you watch a horror movie—a 2013 study found that people watching unpleasant things on video would decrease movement and their heart rate would begin to slow down. The effect of this was immediate, indicating that it was a direct response to what was shown on the screen.

In the fight or flight response, when the threat is over, your body starts to wind back down. It takes 20-30 minutes for the body to recover from your average stress response. Cortisol levels decrease, and your body starts to go back to its everyday functions.

Why do we love horror?

If fear messes up our bodies so much, why do we seek it out?

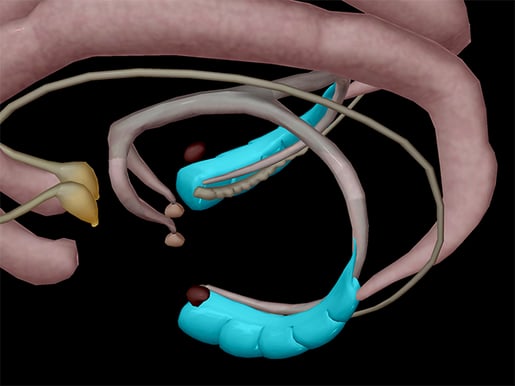

In order to enjoy fear, our brains need to know that there is not a real threat. The hippocampus helps regulate this. The hippocampus is typically associated with long-lasting memories, but it also helps classify memories. In this case, it helps provide context to the amygdala.

The hippocampus, highlighted in blue. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The hippocampus, highlighted in blue. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Some theorize that a movie’s process of suspense and resolution is inherently satisfying. A study from the 1970s showed that children prefer cartoons with elements of suspense. The study does not use horror films, but it underscores that humans love suspense and that sinking feeling of dread helps us enjoy stories more.

Many horror scholars say that horror allows us to work through our fears in a slightly more indirect way. Many horror elements are based on real-life anxieties and problems—take, for example, the top two horror movies of 2020 on Rotten Tomatoes: a film about the refugee experience (His House) and a film about a séance-gone-wrong viewed through a webcam (Host). Even though people sometimes use horror movies as a distraction, they can offer a narrative framework to process what’s going on in the world.

Photo by cottonbro from Pexels.

Photo by cottonbro from Pexels.

After a scary movie or haunted house, some people report feeling positive emotions that keep them coming back for more. Sociologist Margee Kerr conducted a study with 262 haunted house guests and found that the more scared guests felt, the happier they were afterwards. They reported feeling less tired and less anxious, and according to EEG results, those guests experienced a decrease in brain reactivity. Basically, the spooks and scares made some of the brain turn off, which made the haunted house guests feel relieved.

But horror isn’t for everyone; plenty of people do not have positive associations with fear.

A 2009 literature review found that “male viewers, individuals lower in empathy, and those higher in sensation seeking and aggressiveness reported more enjoyment of fright and violence,” though the authors note that men liking horror more might change as gender roles change. Gender stereotypes in horror movies are well-documented, but gender factors into fear, too—traditionally, men are encouraged to not show fear, but for women it’s more acceptable to be afraid. Twelve years later, we have already seen shifts that challenge those findings, as horror movie audiences tend to be 50/50.

Conclusion

When you encounter a threat, your sympathetic nervous system and endocrine system work to quickly release hormones to trigger a faster heartbeat, a faster breathing rate, and other mechanisms that prepare our bodies to keep us safe.

Some people love the thrill the stress response provides. Horror fans love horror for the same reason others hate it: scenes that hit a little too close to home, edge-of-your-seat suspense, and a racing heartbeat.

Another draw for the horror genre is that it’s a social experience, and doing scary things with other people can tighten your bond. Give your sympathetic nervous system a workout and watch something spooky this Halloween!

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.