Digestion's Cutest Heroes: A Dive Into the Intestinal Villi

Posted on 9/12/19 by Madison Oppenheim

Look how cute these little guys are! They may be teeny but they are mighty!

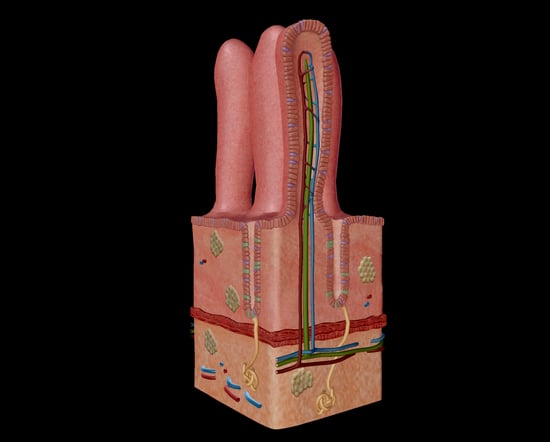

Your intestines are full of tiny villi and even tinier microvilli. These small, finger-like projections extend into the lumen (opening) of the small intestine. Each one is approximately 0.5-1.6 mm long and has numerous projecting microvilli that help you absorb nutrients.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

Click here to explore the images from this blog post in 3D using Human Anatomy Atlas 2021 or later!

Form Follows Function

If I learned anything from sophomore year biology, it's that "form follows function." Let me tell you, when I say that phrase was drilled into my brain, I mean my teacher picked up a cordless impact driver and lobotomized us all one by one. "Form follows function" is just a kid-friendly way of saying anatomy equals physiology. Our anatomy exists solely to serve a specific function. As is the case with most anatomical structures, the more surface area, the better.

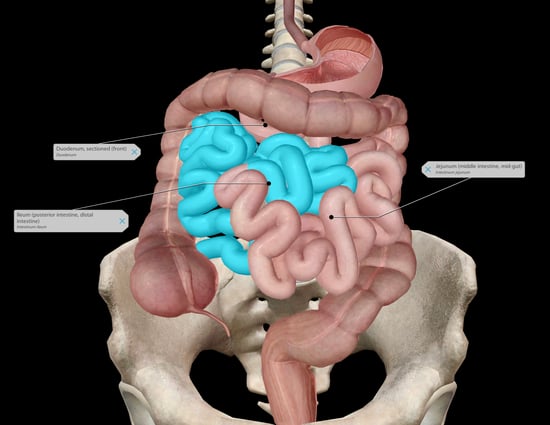

That's especially true when it comes to the gastrointestinal tract. The whole MO of the alimentary canal is maximizing surface area. To the lowly serf, it appears that all we've got is the wiggly 7 m long small intestine and his burlier 1.5 m sidekick, the large intestine. But let me fill you in on all the hot gossip: the surface area for absorption is much, much greater in the small intestine.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

When chyme (partially digested food and gastric juices) is fresh out of the stomach, it's first stop is the duodenum, a short, wide stretch of the small intestine. Here, the chyme mixes with digestive enzymes from the liver and pancreas. Upon relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi, bile secreted by the liver and pancreatic juices secreted by (you guessed it) the pancreas enter the duodenum to help out! They aid in chemical digestion and also help reduce acidity from the strong gastric juices.

Coming in at only 25 cm, the duodenum is the shortest segment of the small intestine. Moving through the GI tract, the next stop is the jejunum. It's got a diameter of about 4 cm and is 2.5 m in length. Here, there are also large circular folds of submucosa called plicae circulares. Lastly, on our journey through the small intestine, we reach the ileum. This is the small intestine's longest segment, coming in at about 3.5 m. The ileum is slightly less vascular and a lighter color than the jejunum, but that's okay, we still love it anyway.

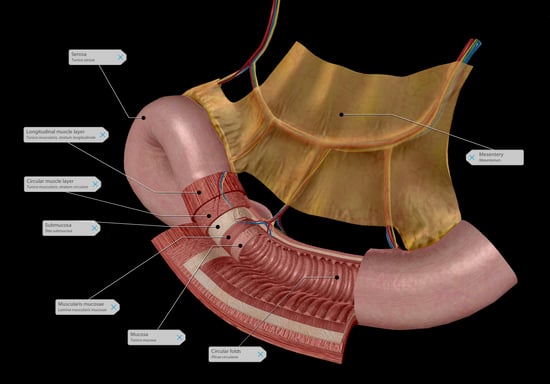

This anatomy lesson wouldn't be complete without first mentioning the structure of the small intestine, because like an onion (or an ogre), it too has layers.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

The outermost layer is the serosa, which is continuous with the mesentery (tissues connecting the intestines to the abdominal wall). It contains blood vessels and nerves, and it secretes fluid to lubricate the small intestine, protecting it from damage due to friction.

Under the serosa is the longitudinal muscle layer. This muscle, in conjunction with the circular muscle (located just under the submucosa), contracts in peristaltic waves, moving food through the intestines. The longitudinal muscle shortens the tract to facilitate the movement of chyme, while the circular muscle prevents chyme from traveling backwards.

The submucosa is composed of dense connective tissue to support the mucosa and connect it to the muscular layers. It also contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves to supply the mucosa.

Next is the muscularis mucosae which comprises several thin layers of smooth muscle. It gently stimulates the mucosa and intestinal glands, helping to expel chyme and enhancing contact between mucosa and chyme in the lumen.

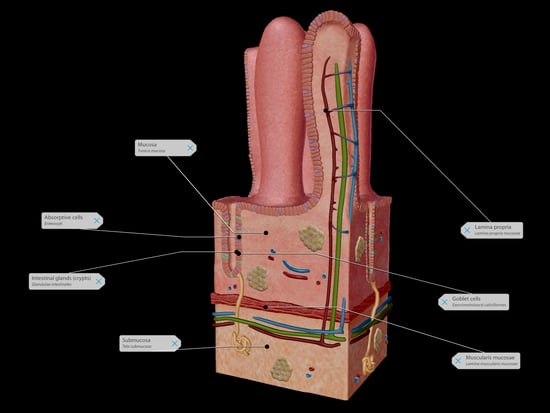

The mucosa is the innermost layer; it surrounds the lumen where the chyme passes. It has three principal functions: protection of the inner environment, secretion, and absorption. The mucosa is incredibly folded, creating...villi.

Enter: The Villi

We made it through the exposition and rising action, now it's time for the big scene where our hero appears to save the day.

The villi, our teensy-weensy finger-like projections, even have their own projections: microvilli. The villi and microvilli create such a large absorptive surface that the surface area of the small intestine is about 250 m2 (almost 2,700 ft2). That's the size of a tennis court!

Human Anatomy Atlas 2020 comes with both the small intestine cross section 3D model I showed earlier, as well as this adorable intestinal villi microanatomy model (and so much more!).

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

The innermost layer of the mucosa comprises simple columnar epithelium with a microvilli-covered surface, called a brush border, that further increases the surface area and consequently, nutrient absorption.

Goblet cells (the purple blobs situated between the absorptive cells in the image), located in the epithelium, secrete mucus into the lumen.

The second layer, the lamina propria, is composed of loose areolar connective tissue that extends into the villi. This contains blood vessels and alkaline mucus-secreting glands that empty into the crypts (intestinal glands) to counter the acidic secretions of the stomach.

The villi and microvilli exist on the surface of the mucosa along circular folds that slow the passage of chyme through the intestines, also increasing the surface area.

I'm sure by now you get it. In fact, if you had a nickel for every time I used the phrase "surface area," you would have exactly $0.35. Neat! I hope you enjoyed this dive into nutrient absorption on the cutest level.

To view a 3D Tour of the images in this blog post using Human Anatomy Atlas 2021 or later...

- Copy this link: https://apps.visiblebody.com/share/?p=vbhaa&t=4_1242_637335349045052910_248500

- Use the Share Link button in the app.

- Paste the link to view the tour.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.