Women's History Spotlight: Five Fantastic Female Scientists You Should Know

Posted on 3/10/21 by Laura Snider

March is Women’s History Month—we thought we’d celebrate by learning about the achievements of five women who made huge contributions to biology, chemistry, physics, and the practice of medicine!

Elizabeth Blackwell: First Female MD in the US

Public domain photo from the National Library of Medicine, accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

Let’s begin with the first woman to become a licensed physician in the US: Elizabeth Blackwell.

Blackwell was born in England in 1821. In 1832, her family moved from England to Cincinnati, Ohio, where she and her mother and older sisters worked as teachers after her father’s death in 1838. Her inspiration to become a doctor came from a dying friend who said that she would have received more compassionate care from a female physician.

In 1847, Blackwell moved to Philadelphia in hopes that some family friends could assist her in applying to medical school. Though she was accepted to Geneva College in New York, the faculty and other students there did not expect her to succeed—those who had voted “yes” to admit her had done so as a joke. The fact that she graduated first in her class in 1849 proved them wrong.

For the next two years, she worked in hospitals in Paris and London, but she returned to New York after purulent ophthalmia caused her to lose sight in one eye.

Elizabeth Blackwell’s contributions to women’s medical education and the education of the public about good hygiene and healthy practices were monumental. Along with her sister, Dr. Emily Blackwell, and their colleague Dr. Maria Zakrzewska, she founded the New York Infirmary for Women and Children in 1857.

Blackwell worked tirelessly for the right of women to become doctors, both in New York and in England, where she traveled often. November 1868 saw the opening of a medical college attached to the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. In 1871, she founded the National Health Society in London to educate the public. She worked with two British doctors, Sophia Jex-Blake and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, to found the London School of Medicine for Women in 1874. Blackwell became a professor of gynecology at the London School of Medicine for Women in 1875.

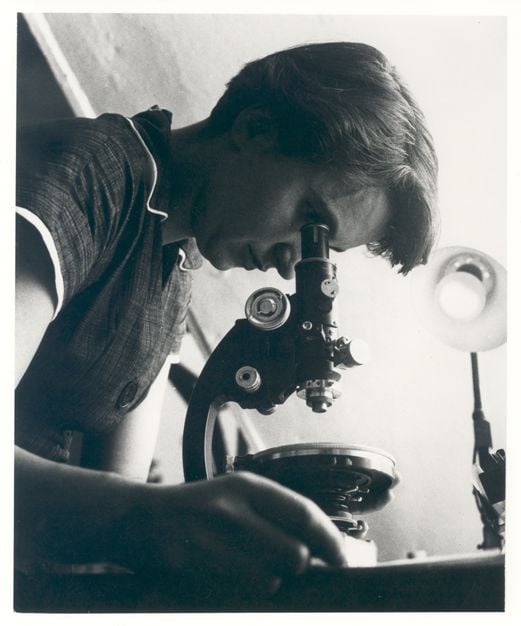

Rosalind Franklin: DNA Detective

Rosalind Franklin in 1955. Photo courtesy of the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, from personal collection of Jenifer Glynn. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons under a CC 4.0 license.

Rosalind Franklin in 1955. Photo courtesy of the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, from personal collection of Jenifer Glynn. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons under a CC 4.0 license.

Today, the double-helix structure of DNA is an image that’s become representative of the study of genetics and biology. The work of chemist and X-ray crystallographer Rosalind Franklin was foundational to our understanding of that famous molecule.

Franklin was born in London in 1920. At 15 years old, she decided that she wanted to become a scientist, and in 1941, she earned her BA in physical chemistry from Newnham Women's College at Cambridge University. Her Ph.D. thesis and much of her subsequent academic work was on the microscopic structure of coal: she “worked to elucidate the micro-structures of various coals and carbons, and explain why some were more permeable by water, gases, or solvents and how heating and carbonization affected permeability.”

After World War II, Franklin moved to Paris, where she worked in Jaques Mering’s lab at the Laboratoire Central des Services Chimique de l’Etat. It was here that she truly honed her skills in using x-ray crystallography (x-ray diffraction analysis) to analyze carbons.

Her work turned to the structural analysis and imaging of biological molecules—namely, DNA—when she returned to England in 1950 in order to join a research team at King’s College.

In 1952, she took a photograph (known today as Photo 51) that would change science forever. This article from the BBC describes the process of capturing this image as follows: “A tiny sample of hydrated DNA was mounted inside and then an X-ray beam shone at it for more than 60 hours. The beam of X-rays scatter and produce an image from which a 3D structure can be determined.”

One of Franklin’s colleagues, Maurice Wilkins, showed this photo to James Watson (yes, he’s the Watson of Watson and Crick) at Cambridge. In his 1986 book, The Double Helix, he recalled the experience of seeing Photo 51: “The instant I saw the picture my mouth fell open and my pulse began to race.The black cross of reflections which dominated the picture could only arise from a helical structure.”

The insights Watson and Crick gained from this image, along with a summary of Franklin’s research, were the final pieces they needed to complete the theoretical model of DNA they had been working on. In 1953, they published the paper for which they, along with Wilkins, would be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962.

Unfortunately, Franklin’s influence on their work was not formally acknowledged until years later. Even more unfortunately, she died of ovarian cancer in 1956, at only 37 years old. Since Nobel Prizes are not awarded posthumously, she did not receive nearly as much credit as she deserves for her work on DNA. The true tragedy of her death was that she likely would have had a bright scientific career ahead of her, full of many more discoveries. Still, her legacy lives on every time we see a rendition of the double helix structure of DNA.

Jane Cooke Wright: Chemotherapy Research Pioneer

Image courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

Image courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

Jane Cooke Wright was born in Manhattan in 1919—her mother was a teacher, and her father was a physician, one of the first African American graduates of Harvard Medical School. She began studying art at Smith College in Massachusetts, then switched to pre-med. She then followed in her father’s footsteps and attended medical school at New York Medical College, and in 1949, she joined him at the Harlem Hospital Cancer Research Center.

Together, they conducted foundational research in the field of chemotherapy. In 1951, Wright published research showing the “efficacy of methotrexate in treating breast cancer.” Her work in the early 1950s was some of the first to test potential chemotherapy drugs on tumor cell samples grown in petri dishes.

When Wright’s father passed away in 1952, she became head of the Harlem Hospital Cancer Research Center. In 1955, she became an associate professor of surgical research at New York University, as well as the director of cancer chemotherapy research at NYU Medical Center and Bellevue and University hospitals. Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Wright to the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke in 1964. That year also saw the beginning of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), of which Wright was a founding member. When she was named professor of surgery, head of the Cancer Chemotherapy Department, and associate dean at New York Medical College in 1967, she became the highest ranked African American woman at a nationally recognized medical institution at the time. In 1971, she was the first woman to be elected president of the New York Cancer Society.

Though she retired from academic work in 1987 and passed away in 2013, Jane Cooke Wright left behind her an impressive legacy of contributions to chemotherapy research—she published 135 papers and received numerous prestigious awards. The ASCO’s Young Investigator Award now bears her name, as does the American Association for Cancer Research’s annual Wright lectureship.

Gertrude Belle Elion: Drug Development Innovator

Gertrude Elion in 1983. Photo courtesy of GSK Heritage archives.

Gertrude Elion in 1983. Photo courtesy of GSK Heritage archives.

Accessed via Wikimedia Commons under a CC 4.0 license.

Gertrude B. Elion was born in New York City in 1918. When she was fifteen, her grandfather’s death from stomach cancer motivated her to “do something that might eventually lead to a cure for this terrible disease.” She completed her BA in chemistry from Hunter College in 1937, graduating summa cum laude, and worked various teaching and research jobs while completing her Master of Science in chemistry at New York University.

In 1944, she joined George Hitching’s research lab at the pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome (which would later become GlaxoSmithKline). While working at Burroughs Wellcome, Elion didn’t just discover new medications—she helped shape the process of modern drug discovery with the principle of “rational drug design.”

Instead of taking a trial-and-error approach to see which drugs worked best to treat particular conditions, Elion and Hitchings reasoned that they could fight disease by disrupting the life-cycle of bacteria and tumor cells using organic compounds called purines (which follow this general molecular structure). If they could stop DNA synthesis, they could stop the growth of these cells.

Elion’s first monumental discovery was a chemotherapy drug called 6-mercaptopurine, or 6-MP, that is still used today to treat leukemia patients. Over the next few decades, she contributed to the development of 45 life-saving drugs. These included Imuran (azathioprine), which suppresses the immune system and made successful organ transplants possible, and the antiviral drug acyclovir, which was used to fight herpes, chickenpox, shingles, and Epstein-Barr. It also paved the way for AZT, the first drug used to treat HIV/AIDS.

Elion, Hitchings, and fellow researcher Sir James W. Black were awarded the 1988 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries of important principles for drug treatment."

Rosalyn Yalow: Radioisotope Investigator

Rosalyn Yalow in 1977. Public domain photo accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

Rosalyn Yalow in 1977. Public domain photo accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

Rosalyn Sussman Yalow, the second woman to win a Nobel prize in medicine, was born in New York City in 1921. She became interested in chemistry in high school, but later majored in physics at Hunter College. In 1941, she was awarded a teaching assistantship at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign—of the 400 members of the Faculty of the College of Engineering, she was the only woman, and the first since 1917.

After earning her Ph.D. in 1945, Yalow returned to teach at Hunter College. In 1947, she joined the Bronx VA as a part-time consultant, researching medical applications of radioisotopes. She devoted her career to research full time in 1950, when she began collaborating with Solomon Berson, a physician. They worked on using radioactive isotopes to “measure blood, study iodine metabolism, and diagnose thyroid diseases.” They then turned their attention to measuring insulin this way, which led them to the work they are most famous for: radioimmunoassay (RIA), a testing method that allows for the detection of very small quantities of specific chemicals in the human body using radioactive isotopes. Their work with RIA and insulin improved diabetes treatment by showing that diabetic people taking cattle insulin were having trouble actually using that insulin because their immune systems were mounting a response. Today, diabetes is treated with human insulin (which is produced by genetically modified bacteria).

In 1968, Yalow became a research professor at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine and chief of Nuclear Medicine Service at the Veterans Administration Hospital. Yalow was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1977—Berman, who had died in 1972, was not able to share the award with her, but she did name the lab at the Bronx VA after him. Before her retirement in 1991, Yalow also received the 1976 Albert Lasker Prize for Basic Medical Research and the 1988 National Medal of Science. Yalow died in 2011, at the age of 89, but her work ushered in a new era in the diagnosis of endocrine conditions. RIA can also be used to detect the presence of viruses such as hepatitis in blood samples, and has therefore made transfusions safer.

There are, of course, many more awesome female researchers and doctors (and scientists outside the field of medicine and medical research!) whose achievements we should celebrate! The National Library of Medicine’s “Changing the Face of Medicine” exhibition is one great place to find more info. The BBC did a great article on this topic last year, and the Smithsonian Magazine, Discover Magazine, and Encyclopedia Britannica also have lists of famous female scientists you can learn more about.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.