Viva the Vagus! Five Facts About the Tenth Cranial Nerve

Posted on 6/7/19 by Laura Snider

Has someone ever told you to “go with your gut,” or have you ever trusted a “gut feeling” without knowing why?

Well, “gut feeling” is a more literal term than we give it credit for. It turns out that the vagus nerve serves as a pretty direct line between your brain and your viscera, keeping track of and reacting to interoceptive signals (that is, information about what’s going on inside your body).

You may remember the vagus nerve as CN X from our overview of the cranial nerves a few weeks back.

Check out our free Cranial Nerves eBook to learn more!

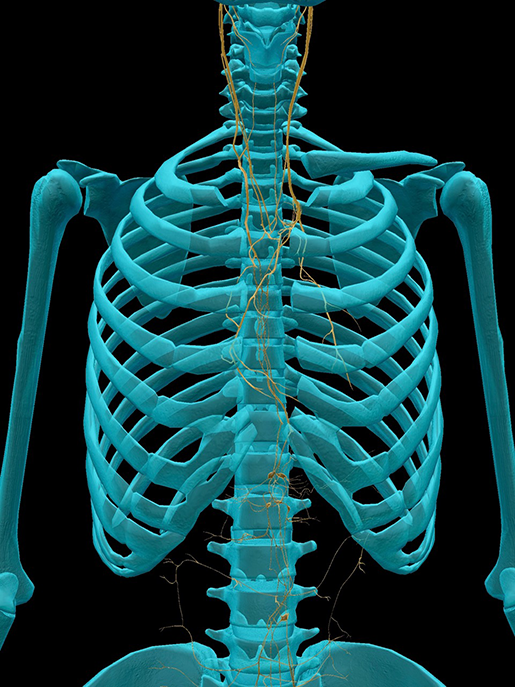

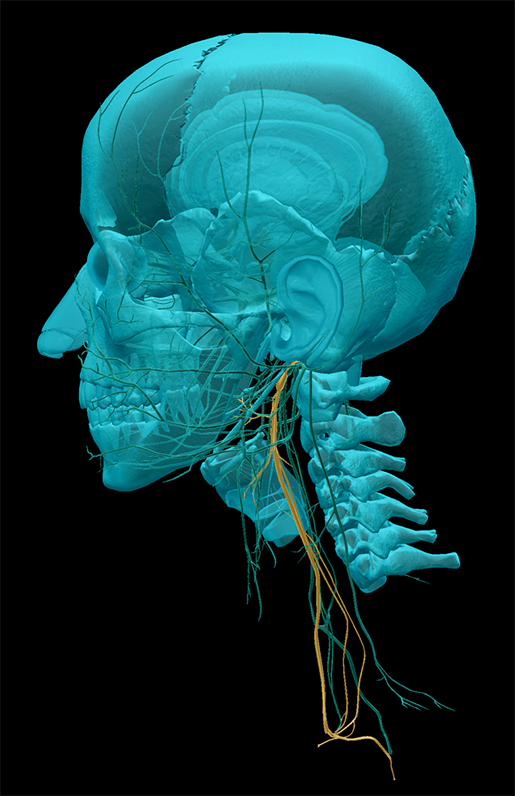

The vagus nerve is the “wandering nerve” that extends from the brain stem all the way down into the torso and abdomen, branching out to your heart, lungs, stomach, and intestines.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Seriously, look at this thing. It’s got its fingers in all the proverbial pies.

So, without further ado, let’s check out five cool facts about the vagus nerve!

1. The vagus nerve links the "gut brain" and the brain-brain.

The enteric nervous system (ENS) refers to the approximately 100 million neurons that regulate blood flow, motility, and secretion within the digestive tract. Though the ENS interfaces with the autonomic nervous system (ANS), it’s independent enough to have its very own reflex arcs. Because of this, scientists often refer to the ENS as the “second brain” or “gut brain.”

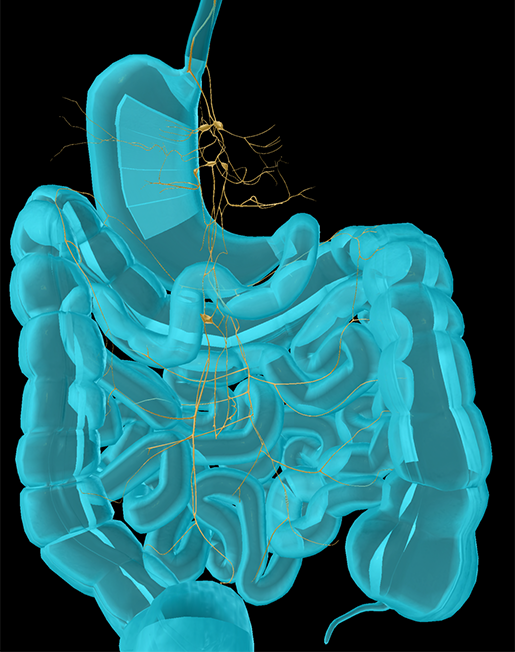

Where does the vagus nerve come in? It serves as the bridge between the ENS and the CNS.

Fun fact: most of the information traveling along the vagus nerve is going in the gut-to-brain direction, keeping the CNS up to date on what’s going on in brain number two. As we’ll discuss in the next section, this gut-to-brain line of communication is important in the regulation of mood and the processing of fear responses.

Anterior vagal trunk, posterior vagal trunk, and celiac plexus. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Anterior vagal trunk, posterior vagal trunk, and celiac plexus. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

On the other hand, when the brain sends signals to the gut, it’s usually preparing the body to “rest and digest” or enter into “fight or flight” mode.

2. The vagus nerve is involved in anxiety and fear responses.

To investigate the connection between mood and the gut-to-brain information pathway, Klarer et al. (2014) looked at the effects of severing the afferent gut-brain connections in the vagus nerve of rats, examining “innate anxiety, conditioned fear, and neurochemical parameters in the limbic system.”

Interestingly, they found that rats without gut-to-brain communication via the vagus nerve experienced lower levels of innate anxiety, but had a harder time “un-learning” conditioned fear responses. That is, they performed well on typical rodent anxiety measures (the “elevated plus maze test, open field test, and food neophobia test”) but their response to auditory-cued fear conditioning persisted longer when compared to control rats. These behavioral changes were linked to differences in GABA and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) in particular areas of the limbic system.

Speaking of neurotransmitters, about 95% of the body’s serotonin can be found in the bowels. If you’re familiar with antidepressant medications, you’re probably aware that a large number of them are SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors). These medications keep serotonin from being reabsorbed, meaning that they make sure there’s plenty of serotonin hanging around in the synaptic cleft between neurons. Because of how much serotonin is in the enteric nervous system, SSRIs can sometimes cause GI tract issues.

3. "Overreaction" of the vagus nerve can cause fainting.

Syncope is the technical term for fainting—that is, when someone loses consciousness for a short time due to a sudden decrease in blood flow to the brain. Vasovagal syncope occurs when the vagus nerve goes into overdrive in response to a stimulus such as the sight of blood, emotional distress, exposure to heat, standing for a long period of time, or even straining to pass a bowel movement.

Essentially, the result of this reaction is a decrease in heart rate and blood pressure. The blood vessels in your legs dilate, allowing blood to pool there. If enough blood can’t reach the brain, you pass out.

Usually, if someone feels like they are about to faint, they are advised to lie down with their feet higher than their head or to sit with their head between their knees. The goal of these strategies is to increase blood flow to the brain and thereby prevent loss of consciousness.

4. Deep breathing affects the vagus nerve.

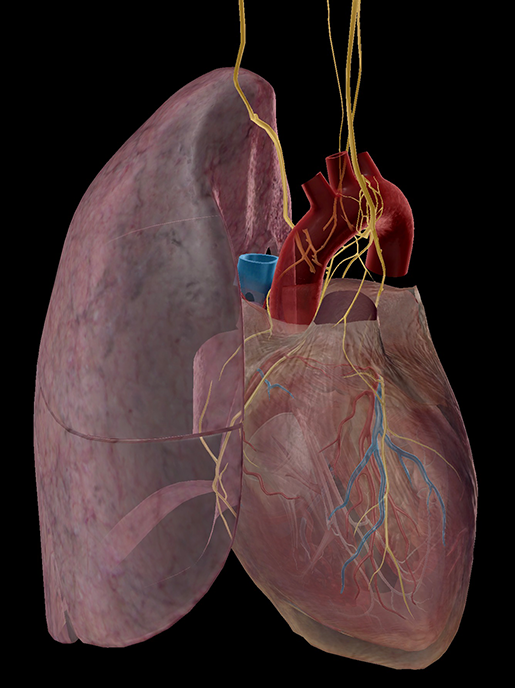

Many people describe deep breathing exercises as a way to “hack” the vagus nerve and achieve relaxation. Basically, what this means is that taking deep, slow breaths helps kick-start your body’s relaxation response, lowering your heart rate and calming you down.

Cardiac and pulmonary plexuses. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Cardiac and pulmonary plexuses. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

“Think of a car throttling down the highway at 120 miles per hour,” Esther Sternberg (a physician and researcher at the National Institute for Mental Health) explained in a 2010 interview with NPR. “That's the stress response, and the Vagus nerve is the brake.” What you’re doing when you’re breathing deeply, then, is easing your foot down on that brake.

If you’ve ever taken a yoga class, you might have done a breathing exercise where your inhalations are shorter than your exhalations (maybe you breathe in for a count of four, then breathe out for a count of eight). A 2018 Frontiers in Human Neuroscience paper showed that in addition to increasing vagus nerve activity, this prolonged-exhalation type of breathing might also engage the parasympathetic nervous system via “vagus nerve afferent function in the airways,” creating “a form of respiratory biofeedback.”

5. Vagus nerve stimulation is used to treat a variety of conditions.

In certain situations, manipulating the connection between the brain and the viscera by electrically stimulating the vagus nerve is helpful. Currently, vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is approved by the FDA for treating treatment-resistant depression. VNS can also be used alongside medications to help manage epileptic seizures.

VNS is typically achieved via a small, surgically implanted pulse generator that is connected to the vagus nerve with thin wires. The generator is flat and round—about an inch and a half in diameter and 10–13 mm thick. Implantation is a relatively short procedure that involves two incisions: one in the upper left of the chest where the generator is implanted, and the other in the left side of the neck where the wires connecting the generator with the vagus nerve are put in.

Left vagus nerve as it travels down the neck. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Left vagus nerve as it travels down the neck. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Once the generator is in place, it can be programmed to activate at particular intervals. At home, patients can use a magnetic bracelet to initiate stimulation as needed.

And there you go: five facts about the awesome and versatile vagus nerve! Next time you use deep breathing to calm yourself down, remember to thank it.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources: