Endometriosis: A Common but Misunderstood Disorder

Posted on 3/11/22 by Sarah Boudreau

Endometriosis may be the most common disorder you’ve never heard of: if you have a uterus and you’re between the ages of 25-40, there’s a 5-10% chance you have or will develop endometriosis. It’s one of the top three causes of infertility and pelvic pain in females, and it’s been estimated that there are 176 million cases globally—but the number of cases can be hard to pin down because many go undiagnosed.

Let’s shed some light on this disorder.

What is endometriosis?

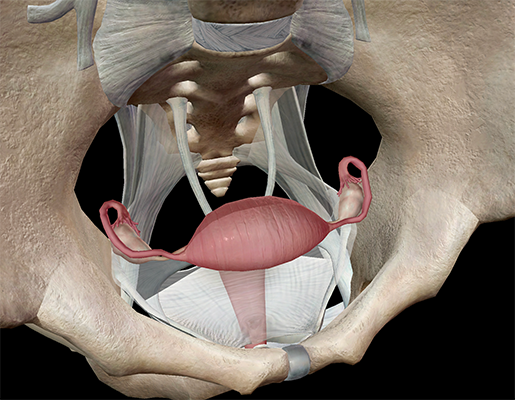

Endometriosis is an inflammatory condition in which tissue that resembles the endometrium (the lining of the uterus) is found outside the uterus. Endometriosis is usually found in the pelvic area, but it can be found elsewhere, like with abdominal wall endometriosis, which usually occurs after a surgical procedure in the uterus, like a C-section. In very rare cases, endometriosis can occur in places like the lungs, spinal column, and nose.

Typical endometrium versus endometriosis. GIF from VB Suite.

Endometriosis causes lesions and cysts to appear, the worst of which are nodules up to five millimeters in length. In addition to infertility, endometriosis can cause severe pain cyclically and during and after sex.

One theory is that endometriosis is caused by retrograde menstruation, where menstrual flow moves in the wrong direction. During retrograde menstruation, debris (including endometrial cells) moves back through the uterine tubes and into the pelvic cavity. It’s thought that endometriosis is caused when endometrial cells stick to these other surfaces, grow in number, and develop their own blood supply.

This theory is supported because those who menstruate more and for a longer period of time are more likely to have endometriosis. Plus, lesions usually occur on the left side, which is consistent with the clockwise peritoneal flow.

However, retrograde menstruation is extremely common, occurring to some degree in more than 90% of menstruating people with patent (open) uterine tubes, so why does endometriosis only develop in some people? Researchers are still trying to determine this.

Other possible causes of endometriosis include:

- Problems with the immune system

- Genetics

- Hormones

Symptoms

Some common symptoms of endometriosis include:

- Severe menstrual cramps

- Chronic fatigue

- Pain during or after sex

- Heavy menstrual flow

- Alternating constipation and diarrhea

Symptoms can depend on where the endometriosis is located—diaphragmatic endometriosis can cause chest and shoulder pain, and endometriosis in the ileocaecal or periappendiceal region can cause abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Image from VB Suite.

Many of these symptoms overlap other conditions, like with adenomyosis, a condition where the endometrium grows into the outer muscular walls of the uterus, causing the uterus to enlarge. You can have both adenomyosis and endometriosis.

One third to one half of endometriosis patients experience fertility problems, but it’s not entirely clear why. It’s thought that, on the mechanical level, pelvic endometriosis could alter anatomy and prevent oocytes from being picked up by the uterine tubes.

Endometriosis can have a huge effect on people’s lives. Not only do people with endometriosis experience pain and fatigue, but that pain and fatigue constantly interrupts their lives. They can miss out on events, school, and work, and they might not be as productive as they’d like—or need—to be, not to mention the emotional toll of infertility.

Diagnosis

Some risk factors associated with endometriosis include:

- Getting your first period before the age of 12

- Having menstrual cycles of under 26 days

- Having a low BMI

- Giving birth for the first time after the age of 30

- Having family members with endometriosis

There are no biomarkers to test for, and laparoscopic visualization is the standard for diagnosis. Laparoscopy can determine the location, size, and extent of the growths.

Ultrasounds can rule out or identify endometrioma, which can be an indicator of deep endometriosis. Endometrioma is when blood is embedded in ovarian tissue and surrounded by a fibrous cyst. MRI can also detect deep endometriosis, but since it’s costly, it isn’t the first imaging technique used. Ultrasound detection is highly dependent on the skill of the operator, so it’s not as reliable.

Endometrioma. Image from VB Suite.

Endometrioma. Image from VB Suite.

There is a four-stage classification system that uses a point system to describe the endometriosis lesions.

- There are not many implants, they are shallow, and they are small.

- Implants are deeper and more numerous than stage I. A mild case.

- Deep implants and possibly endometrial cysts on 1-2 ovaries.

- Many deep implants, large cysts on 1-2 ovaries, and adhesions throughout the pelvic region.

Frustratingly, the stage system isn’t always a useful tool. It doesn’t describe how severe the symptoms are—you can have stage IV endometriosis and be asymptomatic—and the system doesn’t acknowledge endometriosis outside of the pelvic area. It can also be misleading because endometriosis does not advance through the stages like cancer does.

Patients note that clinicians don’t always consider endometriosis as a possibility, or that health professionals underestimate the importance of symptoms. Some don’t seek medical care because they believe their pelvic pain is “normal.” All this can result in delayed diagnosis. In the United Kingdom, for example, it takes an average of 7.5 years to receive diagnosis.

Pelvic area GIF from VB Suite.

Treatment

There is no known cure for endometriosis, so treatment centers around managing symptoms and treating infertility. Management of endometriosis is a long-term endeavor, and treatment will depend on each patient’s age, symptoms, and desire for fertility.

A common treatment for endometriosis is a combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP), which blocks ovulation and reduces estrogen levels. This can reduce pain.

Surgery can remove endometriotic tissue. This is usually effective, but the pain can come back after surgery. Most people prefer conservative surgery—surgery that doesn’t remove the ovaries and the uterus—because they’d like to conceive.

Peritoneal endometriosis (endometriosis in the tissue that lines the abdominal wall and pelvic cavity) and endometrioma can be removed safely, and their removal enhances fertility and decreases pain. However, things get trickier when trying to remove deep endometriosis. For many, a hysterectomy is the best shot for eliminating pain.

Current research on endometriosis

There’s a lot we don’t know about endometriosis, and research is ongoing. Let’s briefly highlight a couple of studies that came out earlier this year.

In a French study published in February 2022, researchers came to a conclusion that departed from previous research. In a study of 1351 participants, they found that endometriosis and risk of preterm delivery are not correlated. As critics have pointed out, however, many different factors can lead to premature birth, and this complexity wasn’t reflected in the study’s design, so it’s possible that endometriosis can influence one or more causes of premature birth but not others.

Research published in January 2022 in JAMA looked at data from 1989-2015 from questionnaires from the Nurses’ Health Study II cohort, which followed participants until they began menopause, turned 45, had a hysterectomy or oophorectomy, were diagnosed with cancer, died, or stopped responding to the survey.

Reproductive system view from VB Suite.

Researchers examined the responses of 106,633 premenopausal women, and analysis found that women with confirmed endometriosis had a 50% greater risk of early menopause.

However, the Nurses’ Health study consisted of 95% non-Hispanic white people and doesn’t represent the diversity of the US or world population. The researchers note that more research should be done before we can come to firm conclusions on the relationship between early menopause and endometriosis.

Even though it affects a significant number of people worldwide, we don’t know a ton about endometriosis. Unlike other long-term conditions like diabetes, endometriosis has been largely ignored in policy and research funding and is not considered a public health priority.

We need more research and awareness so that people suffering from endometriosis can get the help they need!

Teaching endometriosis with Visible Body Courseware

VB Courseware, Visible Body's teaching and learning platform, comes packed with interactive 3D visual content and sophisticated course management tools that make it easy to teach the female reproductive system—including endometriosis.

Courseware allows instructors to leverage VB Suite's vast library of visual assets in their instruction. Through these models, students can:

- View healthy uterus anatomy, including the myometrium and endometrium

- Explore lesions, adhesions on the uterine tube and ovary, and endometriotomas

- Understand how endometriotomas can lead to infertility

- Use the ovarian cycle model to understand the three phases of the ovarian cycle

- Observe changes in fetal anatomy in the first weeks of pregnancy

Endometriosis 3D lesson from VB Suite.

In addition to its library of 3D models, bite-sized learning modules, animations, histology slides, and simulations, Courseware contains a multitude of accessibility tools and features that ensure no student will be left behind. It also has a built-in gradebook that seamlessly integrates with learning management systems like Canvas, Blackboard, Moodle, and more.

To save instructors time and effort, Visible Body has designed premade, customizable curriculum content, including virtual labs and interactive 3D assignments that cover every body system as well as introductory biology topics. You can use the premade female reproductive system assignment to cover the anatomy and physiology of the uterus, and you can either customize the assignment to incorporate the endometriosis 3D lesson or create your own from scratch using Courseware's intuitive, drag-and-drop assignment builder.

See for yourself! You can get a free instructor trial of Courseware here.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.