3 Real Diseases That Influenced Vampire Folklore

Posted on 10/28/20 by Laura Snider

From Bram Stoker’s Dracula to the 2000s’ sparkly Edward Cullen, vampire mythology has been part of popular culture for quite a while. Even before popular books and films were shaping our ideas about these blood-sucking creatures of the night, vampire folklore was present in cultures all around the world.

So...what do vampires have to do with anatomy and physiology (aside from the fact that we here at Visible Body love Halloween)? It turns out that many of the traits and superstitions we associate with vampires come from actual diseases, as well as the biological process of corpse decomposition. Today, we’ll talk about three of these diseases—rabies, porphyria, and tuberculosis—and how they’ve shaped specific aspects of vampire legends from Europe and North America.

1. Rabies

Given that humans usually contract rabies from wild animals, one would expect rabies to be associated with werewolves rather than vampires. However, a 1998 paper in Neurology by Juan Gomez-Alonso put forth a convincing series of arguments that put the symptoms of rabies front and center in many vampire tales. (Also, in some versions of vampire folklore, vampires are what werewolves become after dying, so a common source for both mythologies isn’t that surprising.)

Before we dive into that, let’s briefly go over the basics of rabies. Rabies is caused by rabies lyssavirus, which is transmitted “through direct contact (such as through broken skin or mucous membranes in the eyes, nose, or mouth) with saliva or brain/nervous system tissue from an infected animal.” (Fun fact: the “lyssa” in lyssavirus comes from the Greek word λύσσα, which can mean “rabies” but also “rage” or “fury.”)

The virus infects the central nervous system, ultimately reaching the brain and causing symptoms such as anxiety, confusion, agitation, insomnia, hallucinations, and abnormal behavior before killing the infected animal or person.

The brain and spinal cord make up the central nervous system, or CNS. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The brain and spinal cord make up the central nervous system, or CNS. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Rabies is nearly always fatal if not treated before clinical signs appear. Fortunately, rabies is preventable today. People who are likely to come into contact with infected animals can get a rabies vaccine (thanks, Louis Pasteur!), and people who come into contact with a rabid animal can be treated with postexposure prophylaxis (PEP). PEP is a combination of human rabies immune globulin and the rabies vaccine that are given on the day of initial rabies exposure, and then again on days 3, 7, and 14 post-exposure.

Now back to vampires. In “A Natural History of Vampires,” Eric Michael Johnson provides a thorough summary of Gomez-Alonso’s points. Gomez-Alonso draws a clear parallel between the “depiction of the vampire as a savage beast of prey” and the erratic and potentially violent behavior of rabies-infected humans. In addition, both rabies and vampirism are transmitted via bites or blood-to-blood contact. What’s more, human deaths from rabies tend to result from suffocation or cardiorespiratory arrest. The bodies of people who have died in these ways exhibit signs associated with vampirism—notably, hemorrhage (giving the impression that the person had been drinking blood) and slower decomposition (making it look like the person was not truly dead).

Perhaps the most interesting point Johnson makes about the connection between rabies and vampirism, citing Gomez-Alonso, is that “during the period when dramatic tales of vampires were first emerging from Eastern Europe, a major epidemic of rabies in dogs, wolves, and other wild animals was recorded in the same region between 1721-1728.”

2. Porphyria

While rabies is a likely explanation for the aggressive behavior of vampires and the transmission of vampirism via biting, several other key characteristics of vampires may have been inspired by a blood condition called porphyria. Note that porphyria is not at all an “old-timey” disease—it is a very real medical condition that affects people today. However, before porphyria was well understood, people came up with supernatural explanations for its biological symptoms.

Porphyria is actually a group of related disorders. Most are inherited. There are two broad types of porphyrias—acute porphyrias, which mostly affect the nervous system, and cutaneous porphyrias, which affect the skin. The central issue in all types of porphyria is that there are disruptions in the process that produces heme, which is an essential component of hemoglobin in the blood. Red blood cells contain hemoglobin, which allows them to transport oxygen from the lungs out to the body tissues during gas exchange. Disruptions to heme production lead to the buildup of chemicals called porphyrins in the body.

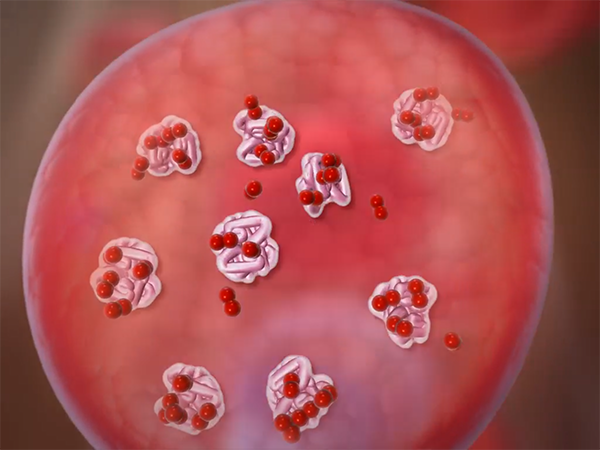

Oxygen molecules (shown as pairs of red spheres) binding to hemoglobin inside a red blood cell. Screenshot from Anatomy & Physiology.

Oxygen molecules (shown as pairs of red spheres) binding to hemoglobin inside a red blood cell. Screenshot from Anatomy & Physiology.

Acute intermittent porphyria is the most common type of acute porphyria. It is characterized by sudden and incredibly painful attacks. According to the Mayo Clinic, symptoms can include:

- Severe abdominal pain

- Pain in your chest, legs or back

- Constipation or diarrhea

- Nausea and vomiting

- Muscle pain, tingling, numbness, weakness or paralysis

- Red or brown urine

- Mental changes, such as anxiety, confusion, hallucinations, disorientation or paranoia

- Breathing problems

- Urination problems

- Rapid or irregular heartbeats you can feel (palpitations)

- High blood pressure

- Seizures

Treatment for acute porphyrias typically involves avoiding attack triggers (certain medications or drugs, hormonal changes, physical or emotional stress, smoking, alcohol use, and/or sunlight) and preventing complications when an attack does occur. Intravenous injection of hemin is often used to return the body’s porphyrin levels to normal.

The most common type of cutaneous porphyria is porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT). PCT is characterized by extreme sensitivity to sunlight. According to the Mayo Clinic, exposure to sunlight can cause the following symptoms in individuals with this form of porphyria:

- Sudden painful skin redness (erythema) and swelling (edema)

- Blisters on exposed skin, usually the hands, arms and face

- Fragile thin skin with changes in skin color (pigment)

- Itching

- Excessive hair growth in affected areas

- Red or brown urine

As with acute porphyrias, treatment of cutaneous porphyrias is focused on reducing exposure to triggers (mainly sunlight) and reducing excess porphyrins. Reducing the iron in the body via blood drawing is one method of decreasing porphyrin levels. Certain medications can also be used to help absorb porphyrins. In addition, people with cutaneous porphyrias often need to take vitamin D supplements to compensate for their avoidance of sunlight.

There are four main connections between porphyria symptoms and vampire folklore. The first is that vampires drink blood. Because porphyria can result in red or brown urine, this may have led to the (false) belief that individuals who demonstrated this symptom had been drinking blood. What’s more, Prof. Michael Hefferon of Queen’s University notes in this blog post that before modern treatments for porphyria, “some physicians had recommended that these patients drink blood to compensate for the defect in their red blood cells — but this recommendation was for animal blood.” This, too, may have fed superstitions about blood-drinking creatures of the night.

Vampires’ famed sun-aversion is likely connected to the symptoms of cutaneous porphyrias such as PCT. People with cutaneous porphyrias usually need to avoid the sun, because sun exposure is painful for them and can cause blistering, burning, and even permanent skin damage. This symptom certainly would have seemed strange to people who lived centuries ago, so it’s unfortunate but not terribly surprising that porphyria’s extreme sun sensitivity became associated with vampire mythology.

Lastly, the ideas that vampires have fangs and hate garlic (or that garlic will harm them) may also have their roots in the symptoms of porphyria. Repeated porphyria attacks can result in facial disfigurement and can cause the gums to recede, resulting in a “fanged” appearance. As for garlic, it has a high sulfur content, which makes it a potential attack trigger for people with acute forms of porphyria.

3. Tuberculosis

Did you know that in the 19th century, Rhode Island was considered to be the “Vampire Capital of America”? Between the late 1700s and the 1890s, vampire superstitions were prevalent in New England—and so was a disease people referred to as “consumption.” Today, we know it as tuberculosis, or TB. Thankfully, TB is rare in the US and there are antibiotics to treat it and a vaccine to protect against it.

Tuberculosis is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a bacterium that typically attacks the lungs, destroying tissue there and potentially killing an infected person if they are not treated properly.

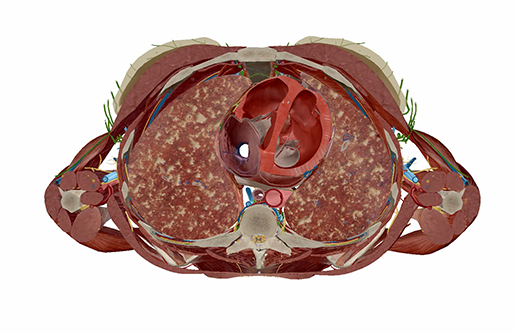

A cross-section of lungs with tuberculosis, showing damage to the tissue. Image from Physiology & Pathology.

A cross-section of lungs with tuberculosis, showing damage to the tissue. Image from Physiology & Pathology.

In the 1800s, it wouldn’t have been too big a stretch of the imagination to think that people who were dying of tuberculosis were having the life sucked out of them by a supernatural creature. People suffering from (untreated) tuberculosis lose weight, become physically weak, have fevers, and cough up blood. In addition, tuberculosis spreads from person to person via the air—when an infected person exhales, speaks, or coughs, someone nearby can inhale TB bacteria. Since most people at that time didn’t know how many diseases spread, “hopeless villagers believed that some of those who perished from consumption preyed upon their living family members.”

This led to a series of disturbing incidents, of which the story of Mercy Brown in Exeter, Rhode Island is probably the most famous. Mercy Brown died of tuberculosis in 1892, and in the weeks after her death, her brother Edwin began suffering the symptoms of tuberculosis. Less than two months after Mercy died, the people of Exeter exhumed her body, as well as those of her mother and sister, who had also died of tuberculosis years earlier. Because so many people in the same family had died of the disease, the townspeople suspected a vampire was at work. When they found Mercy’s body to be more intact than those of her relatives, they decided she was a vampire, removed the heart, burned it, and fed the ashes to Edwin. Not surprisingly, he died (of the tuberculosis he already had).

Fortunately for modern medicine, scientists were beginning to accept germ theory towards the end of the 19th century, and Robert Koch even identified and studied the bacterium that causes tuberculosis, paving the way for a later vaccine. The case of Mercy Brown marked the end of tuberculosis-associated vampire prevention rituals in New England.

Today, most of us don’t have to worry too much about these diseases—we have medications to treat them and vaccines to prevent them. We can be entertained by stories of vampires without living in fear that they will actually drain the life from us.

Have a happy and safe Halloween!

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources: