Five Interesting Facts About Nipples

Posted on 4/4/19 by Laura Snider

The majority of people in the world have nipples. You might giggle at the mention of nipples (maybe because the word “nipple” is so silly-sounding?), but today we are going to demystify them a bit by talking about some interesting anatomical facts!

Before we get to the facts, let’s go over the role nipples play in the basic anatomy of mammary glands (aka breasts). Male and female humans both have breasts in the sense that they both have be-nippled collections of fatty tissue resting on top of the chest wall and pectoral muscles.

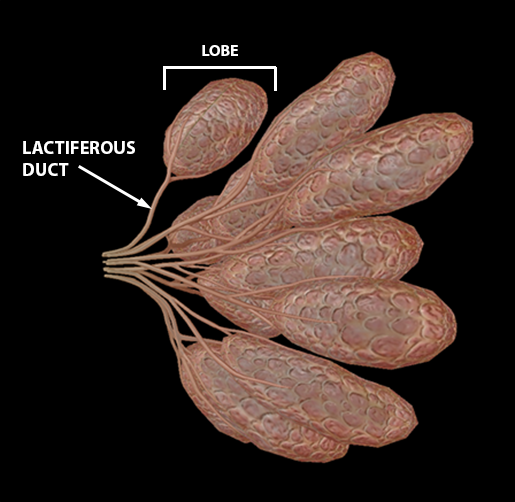

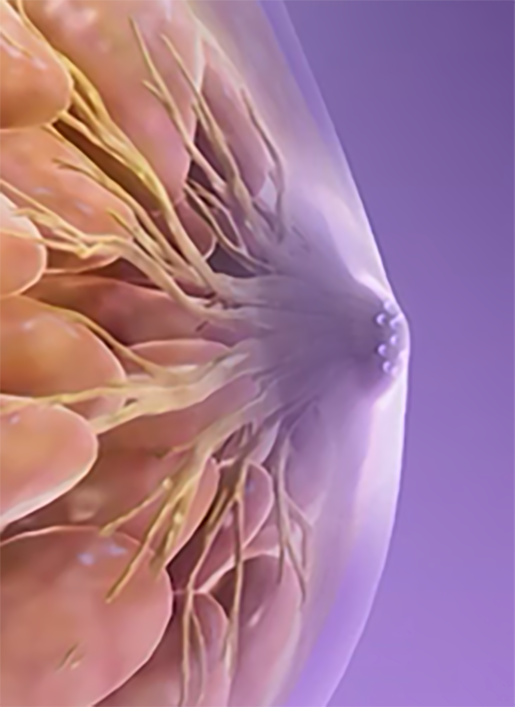

However, female breasts contain milk-producing mammary gland lobules, organized into lobes. Milk drains into a network of lactiferous ducts, ending with the nipple. Here you can see the multiple lobules that make up each lobe, and you can also see how the lactiferous ducts converge towards the nipple.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

All nipples are surrounded by an area called the areola, which is darker in pigment than the surrounding skin. The areolar region is also home to hair follicles and special sebaceous glands called areolar glands (aka Montgomery’s glands), which provide lubrication to the nipple area. The scent of the oil produced by the areolar glands “may even help attract infants to the breast.”

Now, onward to the facts!

1. Nipples and areolas come in a wide variety of shapes, sizes, and colors.

You might think that a nipple is a nipple, but there is actually a lot of variation in their appearance from person to person. The “textbook” nipple sticks out a little from the surface of the breast. It’s referred to as an everted or erect nipple (all right, get your giggles out now), and has a column of smooth muscles to keep it standing up.

Some nipples lie more flat against the breast. Other nipples are inverted instead, appearing as indents in the areola rather than raised structures. If present from birth, inverted nipples are totally normal—if someone has shorter milk ducts, they might also have inverted nipples. However, if an everted nipple suddenly becomes inverted (that is, if nipple retraction occurs), especially if this happens only in one breast, it’s a good idea to consult a medical professional.

Just like nipples, the appearance of areolas varies from person to person as well. Areolas can be small or large, round or oval. They’re typically darker in color than the rest of a person's skin.

Both nipples on an individual body aren’t always identical. It’s not unusual for someone to have nipples that are slightly different from each other in size or shape.

2. Men's nipples are a leftover from embryonic development.

It’s natural to wonder why men have nipples. After all, without milk-producing lobules, there’s nothing for men’s breasts to feed a baby. Ultimately, men’s nipples are just kind of...there. They don’t provide any disadvantages where survival is concerned, so nature’s allowed them to stick around.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

How did they get there in the first place, though? The answer lies in the womb. All typically-developing babies, regardless of their sex, start out with nipples. That’s right—up until sex hormones from the Y chromosome kick in at around 6–7 weeks of gestation and start the formation of the testes in male embryos, development proceeds in essentially the same way for all newly-conceived humans.

Breast development begins at week 4, and ridges called “milk lines” (or ventral epidermal ridges, if you want to sound fancy) appear around week 6, stretching from armpit to groin on each side of the front of the body. Nipples, areolas, and breast tissue form along these ridges.

By the time the male embryo starts producing testosterone (around week 9), the nipples are already in place, a vestigial souvenir of an earlier stage of development.

3. It's possible to have extra nipples or no nipples at all.

Most people have two nipples, one on each breast, but it probably won’t surprise you to hear that there is some variation on that number.

The milk lines we talked about in the last section sometimes give rise to supernumerary—that is, extra—nipples. If an extra nipple appears in a location that’s not along the milk line (which is pretty rare), it’s called an ectopic supernumerary nipple.

The presence of extra nipples is referred to as polythelia. Interestingly, polythelia is more common in men. Most people with polythelia have only one nipple in addition to the two on their breasts, but it’s not unheard of to have more than that. In fact, it’s possible to have up to eight. Extra nipples are often misidentified as moles, since most of them don’t have accompanying breast tissue (though that is possible—it’s a condition called polymastia).

Athelia, the absence of nipples, is also possible. It is most likely to occur in children born with Poland syndrome or a form of ectodermal dysplasia.

4. Nipples and areolas often change size/shape during pregnancy.

Women's’ bodies undergo many changes during pregnancy, and the breasts are no exception.

During the first trimester, the nipples often increase in size, darken in color, and become more sensitive. The areolas become larger and darker in color as well. In addition, Montgomery’s tubercles (the openings of the areolar glands out onto the skin) commonly become more pronounced. They look like little bumps on the areolar region.

During the second trimester, the breasts themselves continue growing as they prepare to produce milk. Starting at about 16 weeks, the breasts produce (and sometimes leak) a fluid called colostrum.

The third trimester sees the nipples becoming even larger and more prominent and the areolas continuing to become larger and darker. Sometimes the nipples can change shape, too.

5. Milk leaves the nipple through multiple tiny holes.

So, we’ve talked about how nipples develop in the womb and how they change during pregnancy, but what role does the nipple play in breastfeeding?

When a baby latches on to breastfeed, the nipple should be pretty far back in their mouth. Most of the bottom half of the areola and some of the top half should also be in the baby’s mouth. This is because when the baby begins to suck at the breast, sensory nerves in the areola tell the brain to tell the body to secrete milk, and the motions of the baby’s lips, tongue, and jaw help draw milk out of the ducts beneath the areola—the ends of these ducts dilate to create a small reservoir of milk beneath the areola.

Video footage from A&P 6.

Video footage from A&P 6.

Did you know that nipples don’t just have one opening? Milk leaves the nipple through a series of between 4 and 18 tiny holes called milk duct orifices or nipple pores. Some are located in the center of the nipple, while others are around the outside of it. Milk duct orifices even have their own little sphincters to keep milk from leaking out.

Image from A&P 6.

Image from A&P 6.

And that completes our list of nipple facts!

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you a professor (or know someone who is)? We have awesome visuals and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources: